Sarah Kabalkin teaches cooking on the North Shore of Staten Island, where she also works with community farms and a community fridge. Mutual aid, food justice and giving back are ingrained in her teaching philosophy. She is a leader of The Sylvia Center’s Staten Island Food Systems Integration Project, an initiative made possible by generous support from New York Community Trust, the Staten Island Foundation, and New York City Council Member Kamillah Hanks.

By Kate Ray

Photographs by Cindy Hu

Sarah: I’ve been with The Sylvia Center for five years. It’s a weird path that I took. I had my first child very young. I dropped out of college, had him, and couldn’t figure out what I wanted to be when I grew up. I changed my major five or six different times, from International Studies to the hospitality program at City Tech. Ultimately, I decided to piece together all of the things I’d gone through in education over 17 years and I created a degree called culinary diplomacy, which touched on basic culinary skills, international cuisine, and political science.

I had this view that I would travel the world and see how food brought people together. Then life just did its own thing; in my last semester of college, I became pregnant unexpectedly. I thought, Okay, well that’s over. I’m not going to be doing any traveling. And then after I had my son I became really, really sick. I wound up in a coma twice. It took me years to recover. When I started to come out of it, I was looking for jobs I could do locally and that’s how I found The Sylvia Center. I realized teaching through The Sylvia Center that all of the things I wanted to do on this international level were needed domestically. I could serve this purpose in my immediate community without having to travel around the world. That’s where this whole thing that I’m doing now got started.

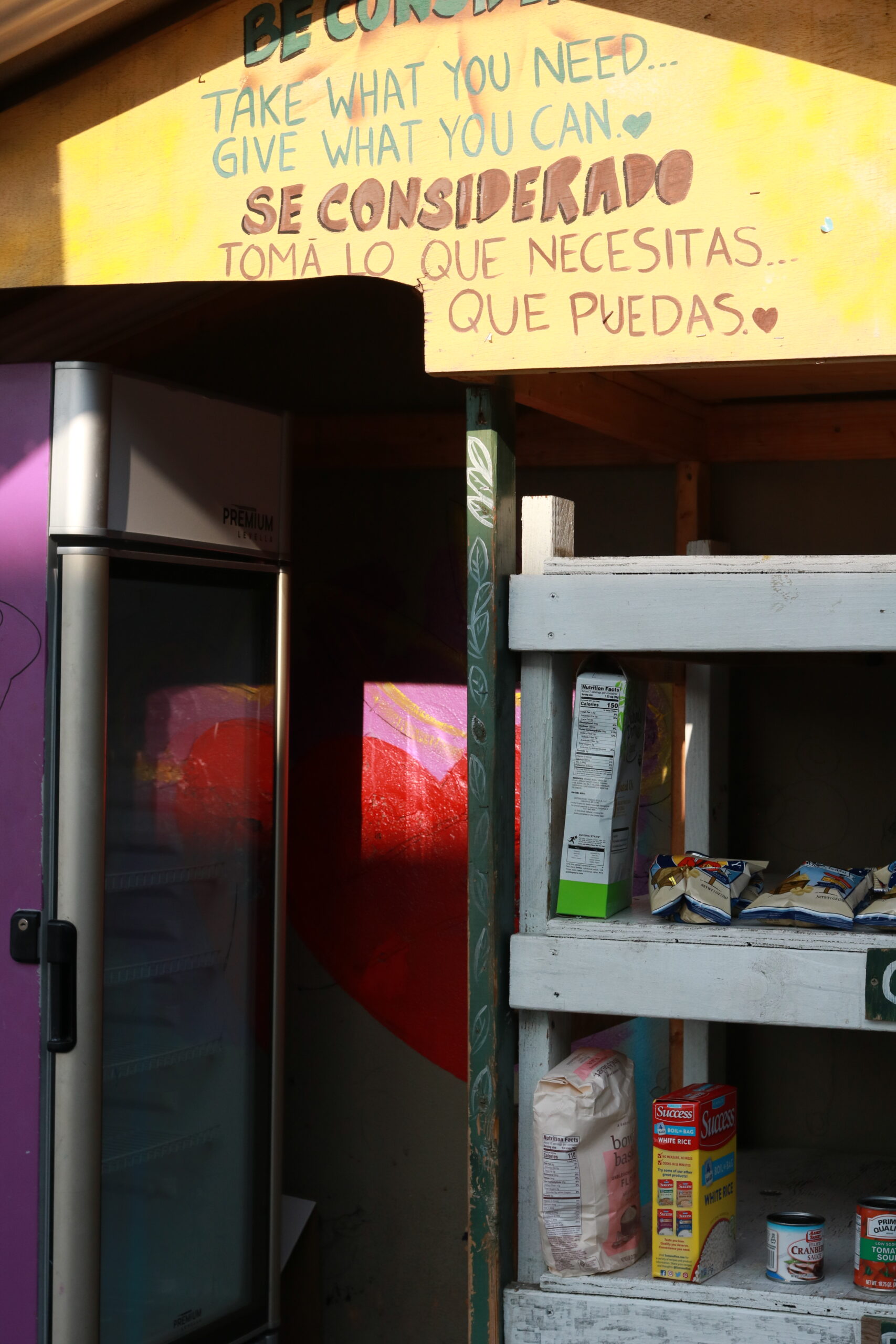

As I was teaching these classes, the community started to see me and ask for more services and over time I developed other programs. I started working with a local organization that has farms in NYCHA and bringing The Sylvia Center students to the farms. I’m a part of a group that started a community fridge here, so we have the kids come to the fridge and work with the community there. They learn about the difference between gardens and farms, how to identify people as food insecure, how to produce the food, how to harvest the food, how to cook the food and what to do with the surplus of food from the gardens. I don’t refer to myself as a Chef Instructor, but rather as a Community Chef, because that really wraps all of it up together.

|

|

|

Kate: Do you have deep roots in Staten Island?

Sarah: Born and raised. Something I think is sometimes missing, is that to really be in the community you have to be a part of the community. Especially in Staten Island. When you walk into a community center to offer a cooking class, they’re like, No you’re not. Who are you? You’re coming in to tell me what to eat and how to eat it? First they need to know that you’re part of the community, that you’re not judging people, that you’re there to share what you’ve learned.

I’m from West Brighton, and that was the center where I was met with the most resistance. So I walked around in my chef coat through the projects, tapping kids on the shoulder playing basketball or sitting in the parks. I said Hey, I’m in the community center. I’m teaching a cooking class, why don’t you come check it out. I relied on some of the OG’s who remembered me, who have a lot of respect in the neighborhood. They came outside with me and said, “Get in the community center. She has something to say.” For so many years I worked hard to get away from the neighborhood, so coming back I had to remember where I was from. That was enlightening for me. I needed some of the people that I distanced myself from to help me come back and be accepted.

Kate: Can you tell me about the role of food and cooking in your life growing up?

Sarah: Food was always a way for me to communicate. I remember I got into a huge fight with my mom once and I wanted to make up for it so I made her potato salad. But I didn’t know that you were supposed to cook the potatoes first. I just cut up potatoes, peeled them, and I made this potato salad and my mom ate it. She said it was good. Then when I tasted it I was like, Oh my god it’s not. She knew I was trying to express myself and she ate it anyway.

I have so many memories of being in the kitchen with my mother and my grandmothers making meals for holidays. Eastern European women tend to stuff food in people’s faces whether they want it or not, because that is their form of communication. The women in my family weren’t cuddly. I don’t remember getting hugs and kisses from my grandmother but I remember there were always homemade cookies on the table.

So being classically trained from school and then knowing the traditional ways from my family, I have two completely separate ways of cooking. When I cook for my family Passover or Hanukkah or Rosh Hashanah, all of those are the old way. There are just some things that you can’t change because if you make too many changes, they don’t taste like grandma. They don’t taste like home. They don’t taste like tradition. In Jewish culture, food is such a strong memory keeper. Every holiday is the retelling of the story of what the Jews have been through, and so when you change food memories, you’re changing the story.

Kate: How do you think about that in terms of your teaching, like what kind of food memories you’re creating for the kids you’re working with?

Sarah: It’s very important for me. I try to get the students to recognize their own traditions and cultures within their food. The recipes I select are significant to the cultures of the students I’m working with, which on Staten Island changes from neighborhood to neighborhood. I like them to have things that they’re accustomed to eating so that we can make some changes, and then have things that they’re not accustomed to so that they can learn about other cultures. Like in West Brighton, the kids wanted to do empanadas. I was focusing on the Three Sisters (corn, beans and squash) and I wanted them to understand the Three Sisters culturally and how it’s used as a sustainability practice. The students and I came up with this whole wheat Three Sisters Empanada and it became a staple in the West Brighton community center. Now, whenever we do something for the community, the high school students make the Three Sisters Empanada.

I would say that as far as food diplomacy goes, I really get to see it in action. Staten Island is probably one of the most divided places I’ve ever been to. There is a very diverse area on the North Shore and a far less diverse area on the South Shore. I’m committed to this idea that food can bring people together across these divides.

There’s a farm in Mariner’s Harbor and on the weekends during the growing season, I’m out there cooking. People now come to the farm and they want to do potlucks. We encourage them to pick up the produce during the week, bring it home, cook it in their style and bring it back. So we have people from all over the world now sitting at a table together, who five years ago were turning their noses up at each other. We sit down and we share food and it’s from the produce that we’ve grown together. It’s culinary diplomacy in action in the community.